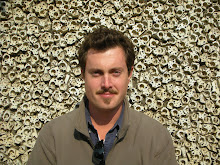

My good friend J. sent me the above link late last night, and it's easily the coolest thing I've seen all week. Noah Kalina has taken a candid self-portrait every day for six-and-a-half years (and counting), stitching them all together over some really ominous piano. It's a fascinating glimpse into a person's life. We are privy to his changing hairstyles, living arrangements, random friends/acquaintances in the background, clothes worn and discarded that magically move from desk to floor to back-of-chair, etc. The expressionless camera-presence is the only relative constant.

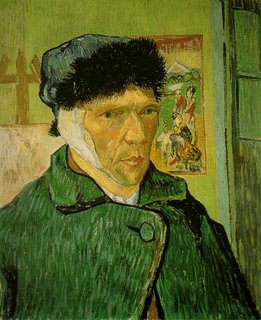

There's something about the immediacy of Kalina's face in these frames, the contextualization of a life-in-progress that goes on in the periphery around the static, almost serene center. It grabbed me in an unexpected way--much as van Gogh's Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear [below right] draws me in, or Schiele's Self-Portrait with Black Vase [below left], or any of Rembrandt's self-portraits with their luminous-yet-still-murky backgrounds. Each of these works makes me stare into the eyes at the same time I'm looking at what else is in the frame, curious to discover how the mind behind a famous face describes itself by what it makes available in the mise-en-scene.

But Kalina's photography here is more raw, less contrived than a painted self-portrait, where the artist must consider each individual brushstroke. To add another layer of reference to this deconstruction, the animation of his snapshots strikes me as almost pointillist. Like Seurat or Lichtenstein, the overall effect when one stands back from the framed work (or, here, the 6 minutes or so of animation) is something greater than the sum of its individual dots. The viewer is left to infer any stories implied by the changing periphery, and the questions that arise etch the piece with all the contours and textures of a 3-dimensional, 360-degree, "real" life: "Why the beaded necklace near the middle of the piece? Who gave it to him? Why did it suddenly disappear?" "Etc., etc., etc..."

But Kalina's photography here is more raw, less contrived than a painted self-portrait, where the artist must consider each individual brushstroke. To add another layer of reference to this deconstruction, the animation of his snapshots strikes me as almost pointillist. Like Seurat or Lichtenstein, the overall effect when one stands back from the framed work (or, here, the 6 minutes or so of animation) is something greater than the sum of its individual dots. The viewer is left to infer any stories implied by the changing periphery, and the questions that arise etch the piece with all the contours and textures of a 3-dimensional, 360-degree, "real" life: "Why the beaded necklace near the middle of the piece? Who gave it to him? Why did it suddenly disappear?" "Etc., etc., etc..."everyday is also a declaration of the power of editing and scoring to alter the meaning of any individual frame in a film. As we have seen recently with the burgeoning craft of "alternative trailers," the image on celluloid is only part of the picture. [My favorite example, taken from one of my favorite films, follows at the end of this post. -N.] By changing the music or the surrounding visual elements of a filmic image, one can effectively re-invent any work in the medium. The Russian film pioneer Lev Kuleshov first described this phenomenon, what would later be called "The Kuleshov Effect." He showed static film of a man's impassive face, then a bowl of soup, then the man's face again, then a coffin, then the man's face, and on and on. Between juxtapositions he would ask his audiences to describe what the man might be feeling. The reaction was overwhelmingly uniform across several versions of the experiment: after the shot of the soup went back to the face, the man was happy because he could eat; after the coffin, the man was sad because someone he knew had died. Keep in mind that the shot of the man's face was the same, changeless and betraying no emotion. What the audience registered was the power of montage, of a filmed moment's context within an edited work rather than as a moment in and of itself. Kalina's blank stare asks his viewers to work the same sort of deduction based on the changing information along the edges of the frame, but at a pace much faster than Kuleshov ever considered.

There's another element at work here that subverts the essential voyeuristic nature of film even as it exploits it. Sure, we have this peek into another's life, and he can't see us watching--but he is staring directly into our eyes from the middle of the frame. It's rare in narrative film to have a character looking directly into the camera (Jonathan Demme uses the technique most unsettlingly in The Silence of the Lambs). It happens more often in documentary film, but for a person to offer, without stutter, "Welcome into my world, my life, my home" from the simultaneous remove and immediacy of a piece like everyday is startling, to say the very least.

There's another element at work here that subverts the essential voyeuristic nature of film even as it exploits it. Sure, we have this peek into another's life, and he can't see us watching--but he is staring directly into our eyes from the middle of the frame. It's rare in narrative film to have a character looking directly into the camera (Jonathan Demme uses the technique most unsettlingly in The Silence of the Lambs). It happens more often in documentary film, but for a person to offer, without stutter, "Welcome into my world, my life, my home" from the simultaneous remove and immediacy of a piece like everyday is startling, to say the very least.Film history lectures aside, a brief admission: it's early yet this rainy Boston Sunday, I've only now hooked up my morning coffee, and everyday was the first thing I saw upon waking after a night of fitful, talkative sleep. I had a definite moment of existential crisis while viewing the piece, wondering where the last six-and-a-half years of my own life have gone while I watched those of another passing before my eyes. I have no doubt that my morning would have been considerably less thoughtful had Kalina scored his epic transformations with, say, The Black Eyed Peas. "Let's Get Retarded" would impart upon the viewer a completely different impression of his work and life than does the current piano score by Carly Comando. Were there also more glaring changes in angle and framing, I probably wouldn't have taken time out of a grey day to write this entry. Behold the power of film, right?

As it stands, this is the kind of project I would advise my kids to undertake as soon as they can wield a camera. It's the perfect complement to a written or video diary (or blog, for that matter), but without all the pressure that a daily catalogue of one's feelings tends to exert over time. A literal fraction of a second each day, and there exists in the digital ether a record of your life in stop-motion. Amazing. Wish I had thought of it years ago. Might start tomorrow. Cheers in the meantime to Mr. Kalina for having the bravery (nay, balls?) to show us the blink-and-you-miss-it passage of time as one man experiences it, at just under 24 frames-per-second.